Introduction

At the Birkdale Neuro Physio, we understand that not everyone has an academic grasp of neurological developments, therapies and approaches. This explanatory guide can assist care givers, patients and other key stakeholders by providing the right knowledge frameworks to help understand the complex processes that surround the functionality of the brain deciphering words. This is a simple task that is learnt from a young age. However, for those suffering from acute brain conditions, this simple task becomes more difficult. This article will help illustrate the process behind the function.

A little background

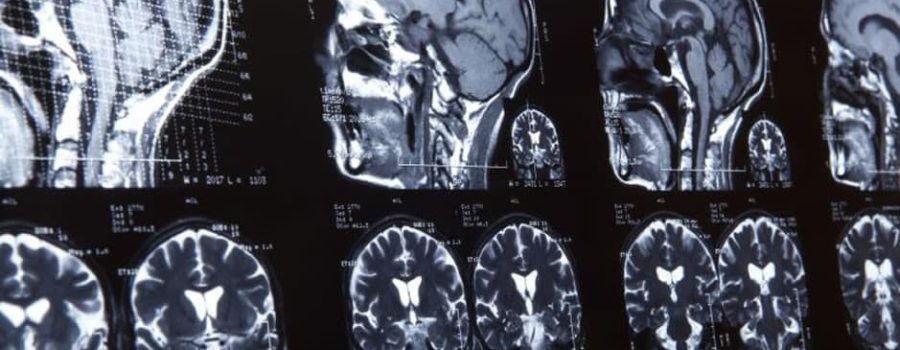

Scientists have long articulated the importance of what is called ‘non-invasive’ imaging of human brain processes courtesy of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). In a range of tested responses, the fMRI scanning technology can help scientists understand a range of human functions and how the brain responds – including how the brain deciphers words. Methodological divergence aside, there is strong consensus that this format of testing has heralded a great leap in academic and medical knowledge and understanding.

Word-based experimentation can help, both in a semantic and non-semantic experience, to highlight neurological function and process. This can be difficult as the cognitive experience of performing the simplest of tasks is difficult to isolate in the context of non-invasive imaging outcomes. Chee, O’Craven, Bergida, Rosen and Savoy undertook such an analysis. Their findings are part of the wider canon of literature that surrounds this research focus. This article will explore their findings and the impact therein on this issue.

The Auditory & Visual Word Processing Study with fMRI

Chee et al. wanted to explore whether semantic auditory and visually presented words processed by the brain presented in distinctive or common areas of the brain. This was to better understand the left temporal and frontal areas and the neuro activities therein during the processing function and therein experience. The key inquiry was to better understand the processing and how it impacted on the brain when scanned by fMRI devices.

The study would have subjects – eight right-handed volunteers aged between 22-38 – who would perform multiple classification tasks in both the auditory and visual forms. Words were presented to volunteers separately. During each presentation, volunteers reacted by performing two tasks – one was semantic (which helped scientists to research the semantic memory of the volunteer) and the other non-semantic (which also helped scientists to understand the non-sematic memory of the volunteer). The word testing explored the dynamics of syllables and lower and upper case as differentiation during the process. Timed intervals also helped to structurally time the process and the functional output.

The Study Results

The main finding was the realisation that reaction time increased during the semantic testing over the non-semantic in both the left temporal and frontal areas. The increase in errors also illustrates the processing within semantic conditioning – which reflected the additional processing time between semantic and non-semantic tasks. In relation to visual versus spoken which also saw a difference in processing time. Visual words appeared almost instantly whilst spoken words took a variable response rate.

What the findings outline is that a mutual semantic system for the processing of auditory and visual words in-activation of the brain during the upper and lower-case testing. This is crucial because previous studies (Petersen et al., 1990; Pugh et al., 1996) argued that brain signal activations from such testing did not appear in semantic vs. non-semantic comparisons. This study highlighted this outcome. However, it also structurally argued that differences in brain activation within individual volunteers performing the same task created a contributory outcome – variances based on topographical brain-based nuances. This reality means that ‘grouped data’ can become contaminated by such findings. However, pooled observations can also help to understand individuality within testing of the same task.

What this means for you?

How does the brain decipher words? The scientific arguments above highlight strong academic and scientific facts that help to create a contextual understanding of the wider issue. However, getting the right support means having access to professional therapeutic specialists who understand neurological issues and the wider experiences, knowledge and research therein. The team at Birkdale can help provide a range of support services aimed at helping to empower patients and care-givers with the right knowledge to help them understand their conditions and their rehabilitation outcomes. Why not get in contact with Birkdale today? Why not call our friendly team on 0208 795 2209 or alternatively email us directly at [email protected] for more information?